How does genocide affect our health in the long term?

Physical status

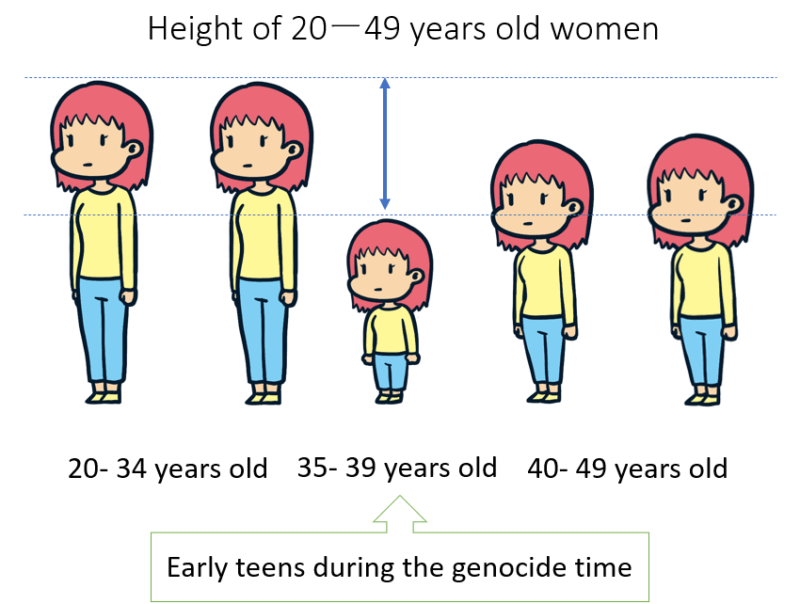

According to a survey conducted in Cambodia in 2000, women aged 35ー39 who were early teens at the time of the genocide had the shortest height among adult women (20ー49 years old).

They likely suffered from general stunting, not just height, suggesting that nutritional deficiencies during adolescence can lead to lifelong short stature.

The same survey in Cambodia showed that the proportion of permanent disability and impairment was high among men who were children and teenagers at the time of the genocide. This is the consequence of exposure to a bomb, a landmine, or a weapon.

Mental status

Many studies show mental problems among people who have suffered from genocide.

A 1995 survey in Rwanda (one year after the genocide) interviewed 1,547 children aged 8ー19.

It revealed that:

– More than 90% of those children were exposed to life threats and witnessed killings;

– 30% of them were witnesses to rape or sexual mutilations;

– 50ー60% of them suffered from “probable Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)“, and it is higher among females than males.

Another study in Rwanda was conducted 17 years after the genocide to investigate the psychological status of people aged 20ー35 years old (who were 3ー18 years old during the 1994 genocide).

The result showed that:

– Mental problems, such as depression, suicidality, and anxiety, are common for both men and women;

– 30ー40% of them suffer from anxiety, 10ー20% from PTSD, suicidality, and depression.

Even after the genocide is over, the survivors continue to suffer mentally and physically for a long time… It makes me sad to think that children have to go through such horrific events.

Does the genocide affect the health of people other than the survivors?

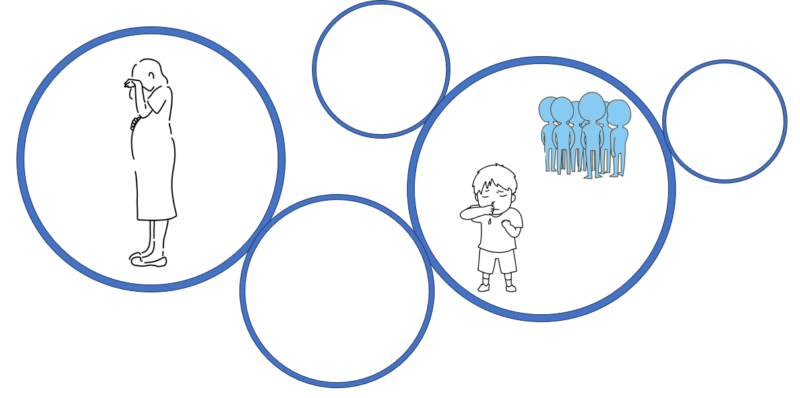

Genocide affects the health of not only survivors but also their children.

A study conducted in Rwanda in 2019 (25 years after the genocide) compared three groups of Rwandan youth (24 years old) on their mental and physical health, and adverse experiences during childhood (e.g., sexual abuse, physical abuse, living with household members with substance abuse, etc):

Group 1: the ones born to women who became pregnant as a result of genocidal rape;

Group 2: the ones born to women who experienced genocide but were not raped;

Group 3: the ones born to women who did not experience genocide or rape (e.g. women who were living abroad at the time of the genocide)

Compared to the other two groups, those born of rape during genocide showed the following trend.

– Significantly higher numbers of adverse childhood experiences

– Significantly higher levels of PTSD and depression

– Suffering more from poorer perceptions of physical functions and bodily pain

What do these results suggest?

It is well known that maternal stress affects fetal development.

Experiencing a genocide already poses significant prenatal stress for a pregnant woman. Furthermore, women who were raped during the genocide often report strong feelings of shame and guilt, which also poses significant stress for themselves and their fetuses.

Children born as a result of genocidal rape often feel intense shame about their origins and face discrimination within their families and communities.

Pre-natal, postnatal, and early childhood stresses not experienced by others have lifelong implications for poor physical and mental health.

I think it’s nonsense that they suffer so many problems and are discriminated against even though they have done nothing wrong.

How does genocide affect people beyond their own health?

In addition to individual health problems, genocide also disrupts health systems and destroys infrastructure.

For example, countries face shortages of health workers, as many doctors flee the country or are killed during the genocide.

With many health facilities destroyed, the delivery of treatment is disrupted and vaccination schedules for children are interrupted.

Recovering from these damages takes a lot of time and money.

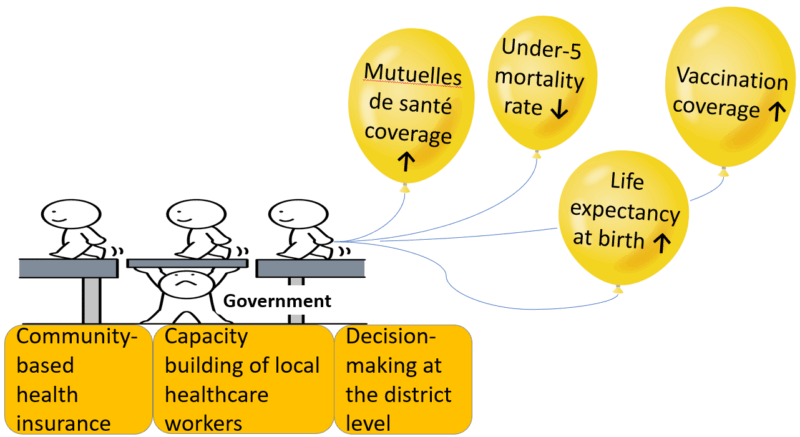

Here, let’s look at Rwanda’s efforts, showing the dramatic success of the health care system recovery after the genocide.

After the 1994 genocide, the government guided health policy reforms with strong leadership and governance.

The government developed a national health service delivery system and a health information system. It did not allow NGOs to operate alone but required them to work in partnership with the government.

In addition to the strong governance at the central level, it decentralised the decision-making at the district level and increased the capacity of local healthcare workers.

The government also implemented community-based health insurance, named Mutuelle de santé.

The characteristics of this health insurance are:

– More than 80% of the population is currently under this health insurance (as of 2025).

– Most people pay about 2 USD per year;

– The health insurance covers drugs and medical services provided from the local health unit to the national level (health posts, health centres, district/provincial hospitals, and the referral hospitals);

– Some treatments are not covered by this scheme, but more treatments are added every year. The treatment for breast cancer was added in 2025.

– This system minimises out-of-pocket medical expenses for citizens and provides better access to health care at an affordable price.

As a result of their efforts, Rwanda’s health situation has improved:

– Life expectancy at birth increased significantly;

– The death rate of children under 5 years old decreased; and

– The vaccination coverage rapidly improved from 30% in 1995 to 94% in 2015.

The experience of genocide is horrific, but I am very happy to hear about the improvement of the health system in Rwanda. Once the genocide is over in Gaza, we will have to work hard like this together.

References

– Rieder, H., Elbert, T. Rwanda – lasting imprints of a genocide: trauma, mental health and psychosocial conditions in survivors, former prisoners and their children. Confl Health 7, 6 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-7-6

– Neugebauer R, Fisher PW, Turner JB, Yamabe S, Sarsfield JA, Stehling-Ariza T. Post-traumatic stress reactions among Rwandan children and adolescents in the early aftermath of genocide. Int J Epidemiol. 2009 Aug;38(4):1033-45. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn375. Epub 2009 Feb 8. PMID: 19204009.

– Rugema L, Mogren I, Ntaganira J, et al. Traumatic episodes and mental health effects in young men and women in Rwanda, 17 years after the genocide. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006778. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014006778

– Uwizeye G, Thayer ZM, DeVon HA, McCreary LL, McDade TW, Mukamana D, Park C, Patil CL, Rutherford JN. Double Jeopardy: Young adult mental and physical health outcomes following conception via genocidal rape during the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. Soc Sci Med. 2021 Jun;278:113938. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113938. Epub 2021 Apr 15. PMID: 33905987.

– Shriya Yarlagadda. Harvard International Review. Growth from Genocide: The Story of Rwanda’s Healthcare System. 07. Mar.2022. https://hir.harvard.edu/growth-from-genocide-the-story-of-rwandas-healthcare-system/

– Emeli IM. The Rwandan Healthcare System: Can a Shifting Burden of Disease Threaten a Post-war Success Story? Cureus. 2024 Feb 10;16(2):e53957. doi: 10.7759/cureus.53957. PMID: 38468981; PMCID: PMC10926934.

– Iyer HS, Chukwuma A, Mugunga JC, Manzi A, Ndayizigiye M, Anand S. A Comparison of Health Achievements in Rwanda and Burundi. Health Hum Rights. 2018 Jun;20(1):199-211. PMID: 30008563; PMCID: PMC6039746.

– Benjamin Chemouni, The political path to universal health coverage: Power, ideas and community-based health insurance in Rwanda, World Development, Volume 106, 2018, Pages 87-98, ISSN 0305-750X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.01.023.

– Rwanda Social Security Board. CBHI Scheme. https://www.rssb.rw/scheme/cbhi-scheme

– Health Policy Watch. In Rwanda, Decentralised Health Coverage Starts With Community Health Workers. 26 Feb 2025. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/in-rwanda-decentralised-health-coverage-starts-with-community-health-workers/