What health problems do children in poverty have?

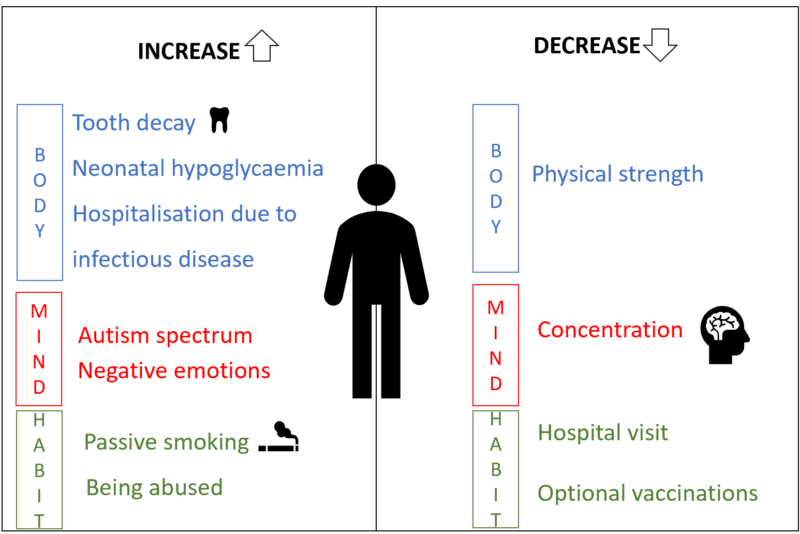

The impact of poverty on children’s health has a wide range of effects on their bodies, minds, and behaviours.

In terms of food, the following trends are observed in poor households in Japan:

- The frequency of skipping breakfast is significantly higher.

- Around 30% of them do not take 3 meals a day.

- The intake of carbohydrates increases.

- The intake of proteins, minerals, and vitamins decreases. It leads to a decline in physical strength and concentration.

Research has shown that people in poverty are hospitalized more frequently due to infectious diseases than people with higher incomes.

Poverty lowers children’s sense of well-being and lowers their self-esteem.

There are also differences in lifestyle habits and behavioural patterns.

Due to time and financial constraints, people in poverty tend not to go to the hospital even if they feel unwell.

Vaccination rates for voluntary vaccinations are reduced because they require payment.

Other risks include increased exposure to passive smoking and abuse.

In some countries, autism spectrum disorders are more common among wealthy families. Please check out the trend in your country.

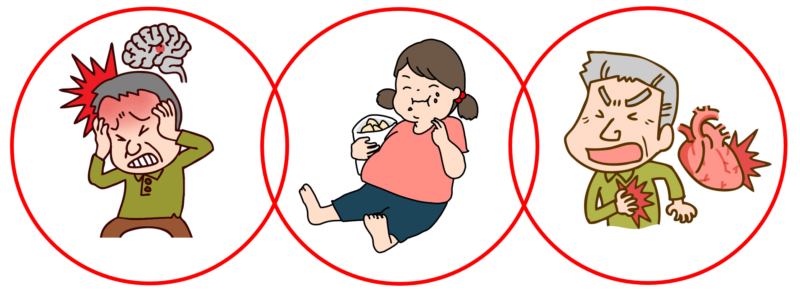

Does poverty in childhood affect adults’ health when they grow up?

Poverty affects not only children’s health but also their health in adulthood.

The method of studying these relationships is called the Life Course Approach.

In the research process, various factors are observed from the fetal period in the mother’s body, through childhood, adolescence and adulthood.

This can show how childhood poverty affects long-term health outcomes and which diseases can be a risk in adulthood.

For example, childhood poverty is associated with obesity in adulthood and has a higher risk of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes in adults.

These problems are due to not having proper eating habits and lifestyle habits in childhood.

To reduce the risk of diseases in adults, we need to address poverty among children.

Is there anything the health facility can do?

In the examination room, doctors usually focus on finding diseases and are unlikely to look into a patient’s financial situation unless the patient complains.

However, by focusing on trends in patients’ illnesses and treatments, healthcare staff may be aware of socio-economic problems in patients’ families.

The following points can help healthcare staff notice the poverty of patients:

- Delay in seeing a doctor (e.g. not seeing a doctor until symptoms become severe)

- Hesitate to take a test

- Save money on medicines

- Poor understanding of drug usage and dosage

- Have chronic diseases and poor understanding and attitude toward treatment

- Too many cavities or missing teeth

- Take time to notice and bring children to a hospital for disabilities and illnesses

By understanding a patient’s financial situation, medical professionals can connect the patient with welfare services and use a public program such as free or low-cost medical services (in Japan).

This program targets people in need, such as low-income earners and the homeless.

If they receive treatment at a registered hospital, within the scope of medical insurance coverage, the treatment would be free or at a low cost.

Free or low-cost medical care is helpful for people in poverty. That is a very good public service, but it’s not well known. It is important to disseminate information more to the public.

References

– Tokyo Metropolitan Government Research Council. Report on research into child poverty prevention measures in basic local governments. https://www.tama-100.or.jp/contents_detail.php?co=kak&frmId=667

– Takashi Igarashi. Journal of Home Economics of Japan. Child poverty from the perspective of health and medical care. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jhej/69/11/69_775/_pdf

– Yasue Ogata, Mie Yokoyama. A literature review on economic inequality and children’s health. Osaka City University journal of nursing, Vol. 15 (March 2019). https://dlisv03.media.osaka-cu.ac.jp/contents/osakacu/kiyo/24347779-15-17.pdf

– Aya Abe. Factors behind health disparities in children: Are there differences in the ability to recover from past health problems? Medical and Social Sciences Vol.22 No.3 2013. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/iken/22/3/22_255/_pdf

– Masayuki Kase, Kobun Wakashima. The relationship between child poverty and mental health: focusing on experiences of deprivation due to poverty. Bulletin of the Psychological Support Center, Vol. 2,2023,73-89. https://tohoku.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/2000040/files/psc-2023-2-73.pdf

– Li Qingya. Childhood family environment and health disparities: An analysis of obesity factors. Quarterly Social Security Research. Vol. 49 No. 2. 217-229. https://www.ipss.go.jp/syoushika/bunken/data/pdf/19857406.pdf

– Kunitachi Gastroenterological and Endoscopy Clinic. What are the “four happy hormones (happiness substances)”: dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, and beta-endorphins? https://kunitachi-clinic.com/column/%E3%80%8C%E5%B9%B8%E3%81%9B%E3%83%9B%E3%83%AB%E3%83%A2%E3%83%B3%EF%BC%88%E5%B9%B8%E7%A6%8F%E7%89%A9%E8%B3%AA%EF%BC%894%E3%81%A4%E3%80%8D%E3%83%89%E3%83%BC%E3%83%91%E3%83%9F%E3%83%B3%E3%83%BB%E3%82%BB/

– Takeo Fujiwara. Prevention of adult diseases from fetal and childhood stages through a life course approach. J Natl. Inst.Public Health, 56 (2), 2007, 90-98. https://www.niph.go.jp/journal/data/56-2/200756020006.pdf

– Thinking about health and society. Japan Primary Care Association. https://www.primarycare-japan.com/news-detail.php?nid=266

– Tokyo Metropolitan Government Bureau of Social Welfare. Free and low-cost medical treatment program and free and low-cost nursing care facility utilization program. https://www.fukushi.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/seikatsu/hogo/mutei.html#:~:text=%E7%84%A1%E6%96%99%E4%BD%8E%E9%A1%8D%E8%A8%BA%E7%99%82%E4%BA%8B%E6%A5%AD%E3%81%A8,%E8%A8%BA%E7%99%82%E3%82%92%E8%A1%8C%E3%81%86%E4%BA%8B%E6%A5%AD%E3%81%A7%E3%81%99%E3%80%82